AI chatbots have become a visible source of traffic for Russian propaganda websites under EU sanctions, channelling hundreds of thousands of visits in a single quarter and, in some cases, forming a significant share of these sites’ referral traffic. This shows how generative AI is quietly integrating sanctioned Kremlin-friendly outlets into everyday information journeys for users across Europe.

In this research, we have analysed the traffic that AI chatbots generated in the fourth quarter of 2025 to Russian propaganda websites covered in SimilarWeb data. Between October and December 2025, major AI tools generated altogether at least 300,000 visits to eight Kremlin-linked or pro-Russian websites, including RT and Sputnik domains.

The traffic originated from conversational AI platforms such as ChatGPT, Perplexity, Claude, and Mistral, which increasingly function as “answer engines” rather than simple productivity tools. While the absolute numbers remain small compared with overall news website traffic, the pattern points to a new and largely unregulated distribution channel for state-aligned media.

AI chatbot traffic to Russian propaganda websites

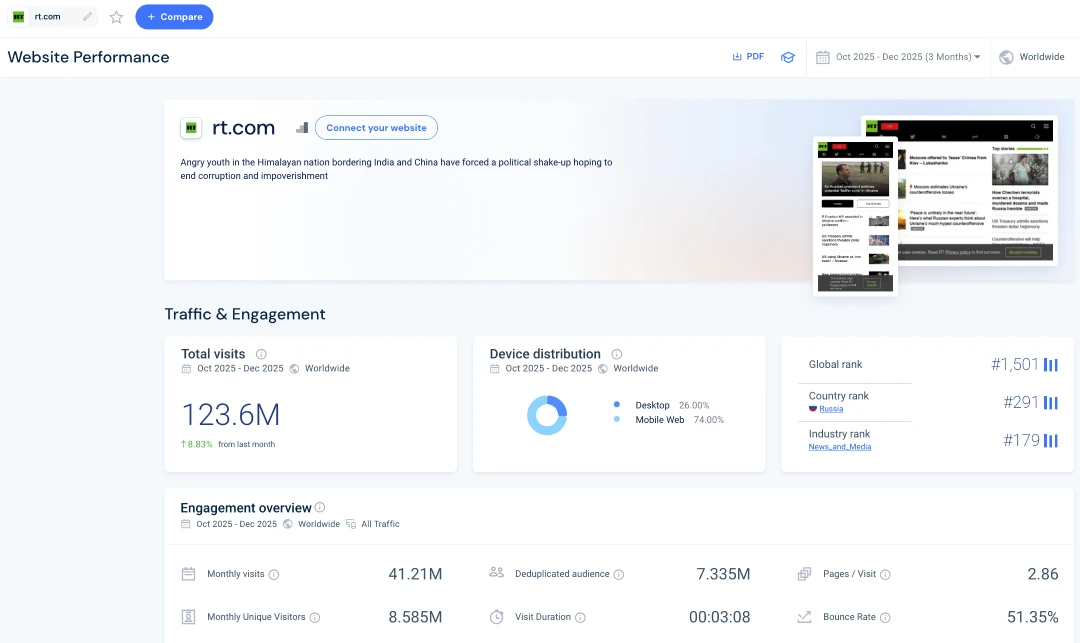

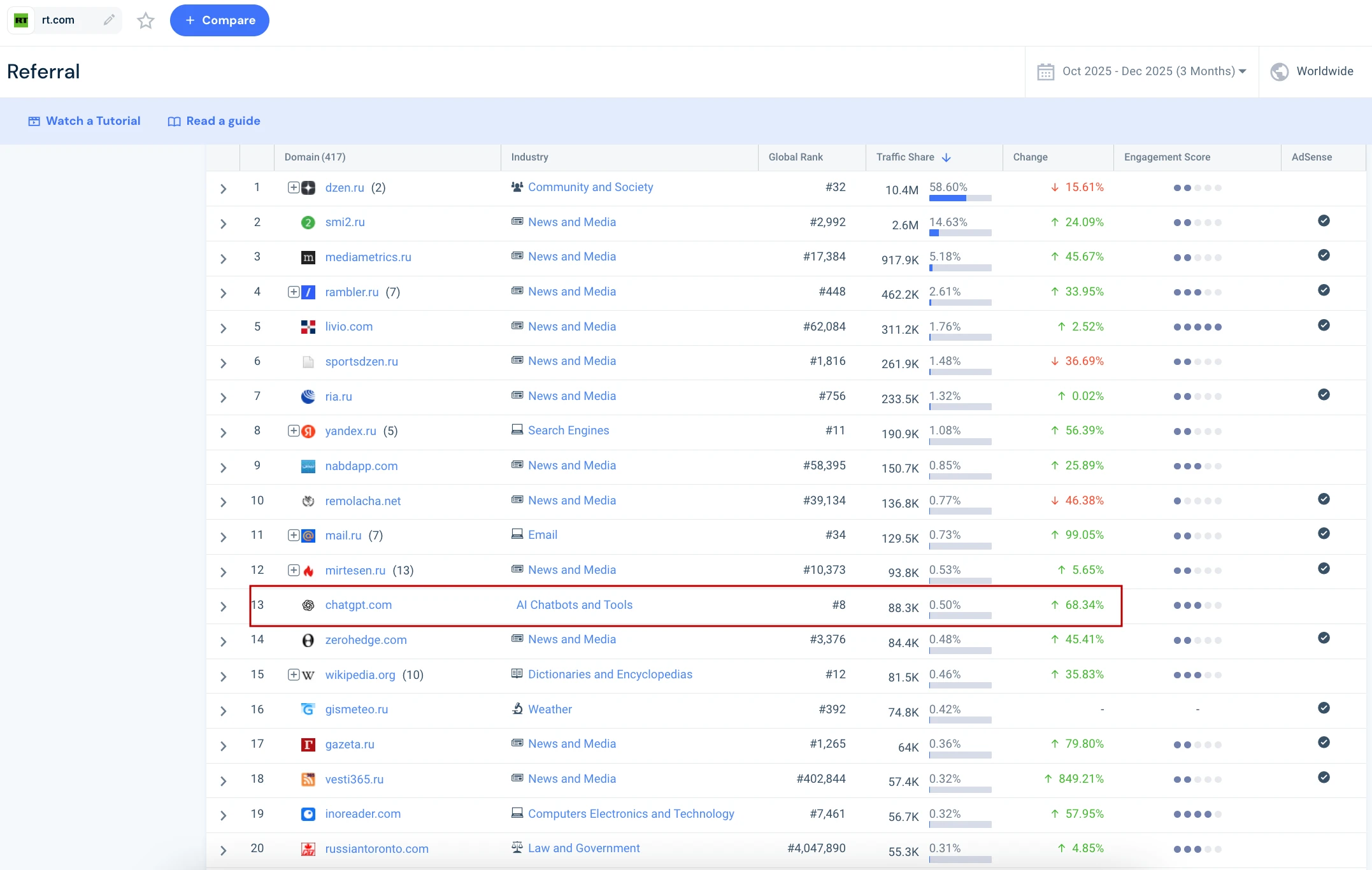

For large outlets like RT, AI referrals represent a fraction of total audience reach. RT recorded more than 123 million page views in Q4 2025, and AI-driven visits accounted for well under one per cent of that total. Even so, ChatGPT alone sent more than 88,000 visits during the quarter, while Perplexity contributed just over 10,000.

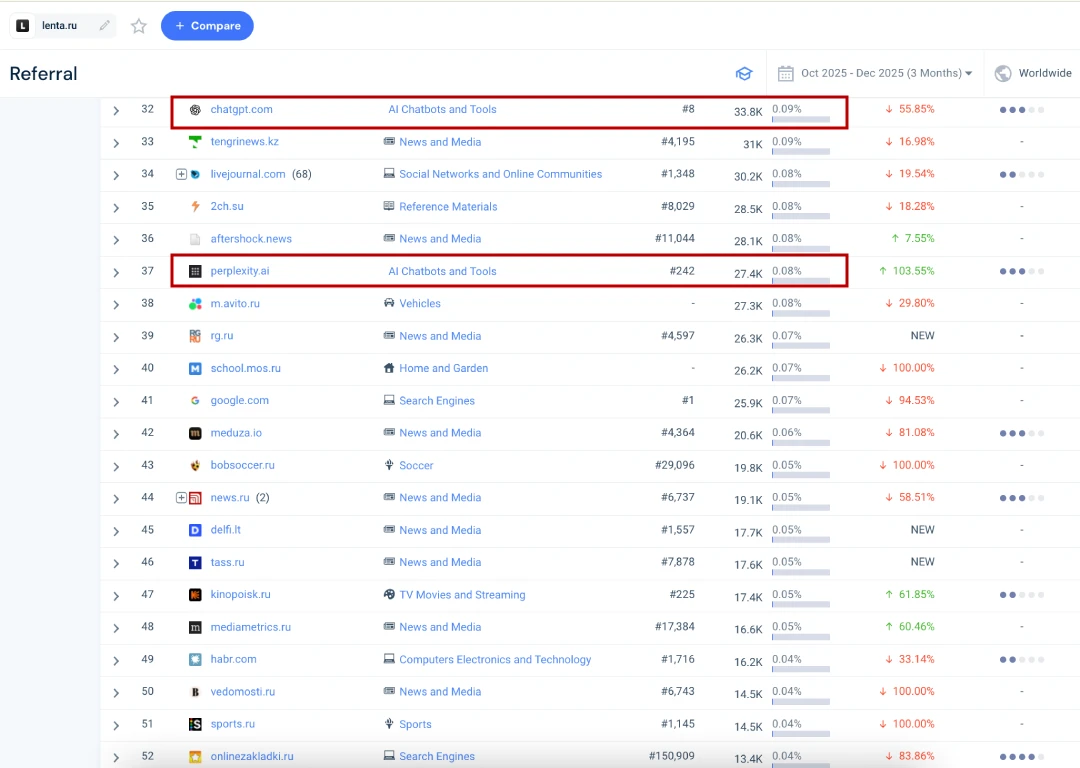

Similar patterns appear across other major Russian-language outlets. RIA Novosti received more than 70,000 AI-driven visits, while Lenta.ru recorded over 60,000. In several cases, Perplexity appeared as a new referral source in the same quarter, suggesting that AI-driven discovery is still expanding.

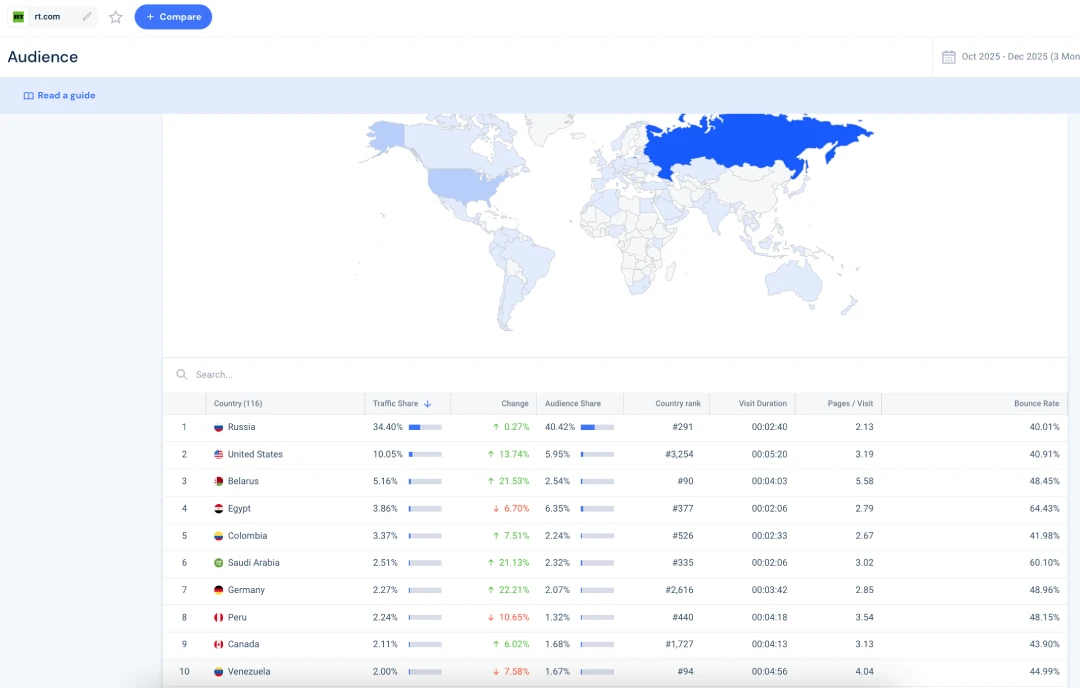

The geographic distribution of these audiences complicates the picture. Despite sanctions and restrictions, a significant share of traffic to sanctioned outlets still comes from EU member states and the United States. AI referrals are feeding into the same international audience pools that sanctions are meant to constrain.

What’s unsettling is the geography overlap. RT’s audience mix still includes the US (10%), Germany (2.27%), Spain (1.48%), and the UK (1.12%), even though these are precisely the kinds of markets where restrictions are meant to reduce reach. AI does not “break” sanctions by itself, but it can make sanctioned sources feel like just another link in a helpful list.

Methodology and Scope

The data comes from SimilarWeb data for Q4 2025 (October–December 2025) on eight Russian state or pro-Kremlin propaganda websites sanctioned in Europe for spreading disinformation and supporting Russia’s war against Ukraine. We focused on referral traffic from major AI tools (ChatGPT, Perplexity, Claude, and Mistral) and on the overall audience size and geography of the recipient websites. Here below is the dataset’s core referral picture from the AI tools used by news searchers, as defined by SimilarWeb (ChatGPT, Perplexity, Claude, Mistral):

- rt.com: 98.4K combined (ChatGPT 88.3K, Perplexity 10.1K)

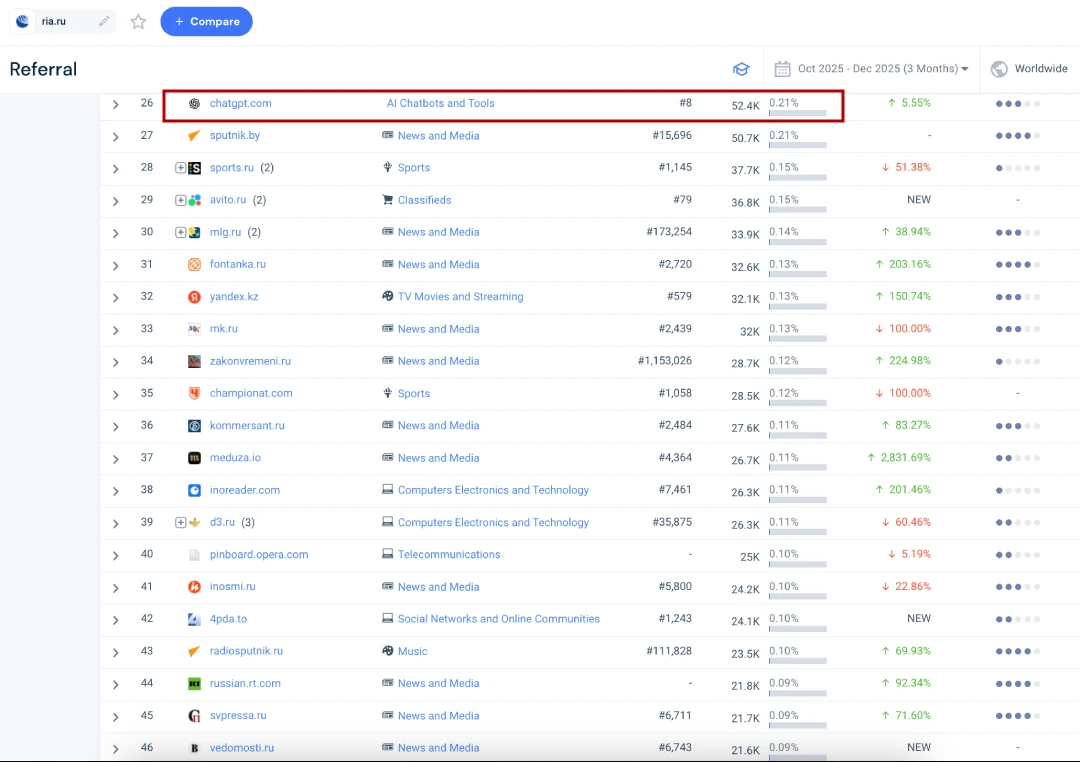

- ria.ru: 72.2K combined (ChatGPT 52.4K, Perplexity 19.8K)

- lenta.ru: 61.2K combined (ChatGPT 33.8K, Perplexity 27.4K)

- iz.ru: 22.1K (ChatGPT)

- rg.ru: 18.6K combined (ChatGPT 13.2K, Perplexity 5.4K)

- reseauinternational.net: 5.8K (ChatGPT) plus Mistral under 5K

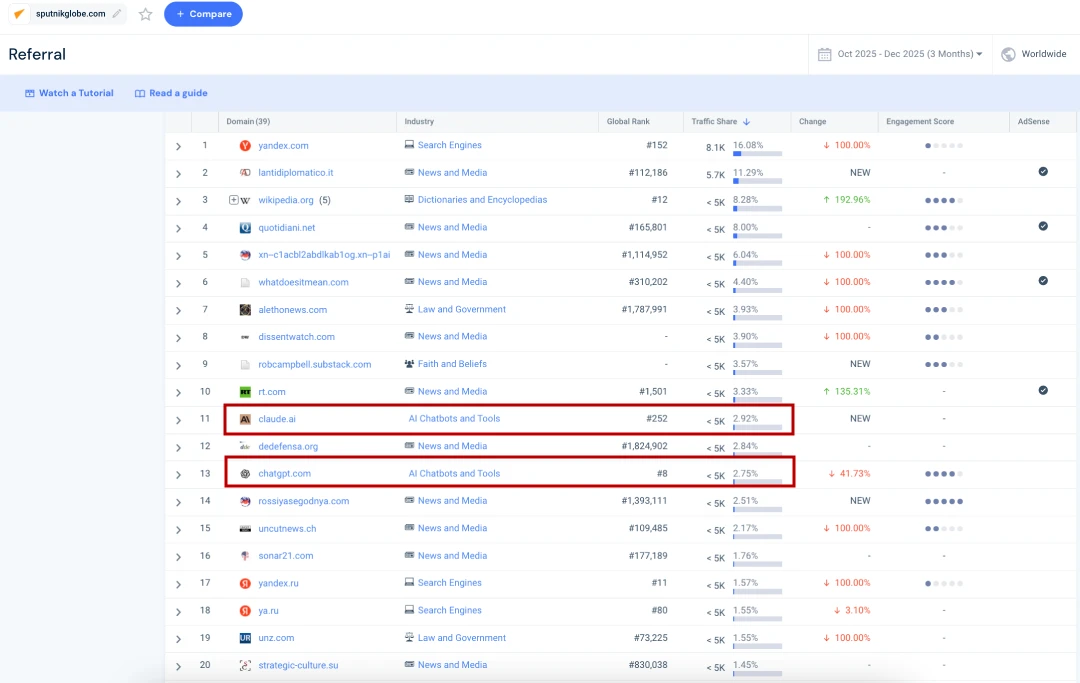

- sputnikglobe.com: under 10K combined (ChatGPT under 5K, Claude under 5K)

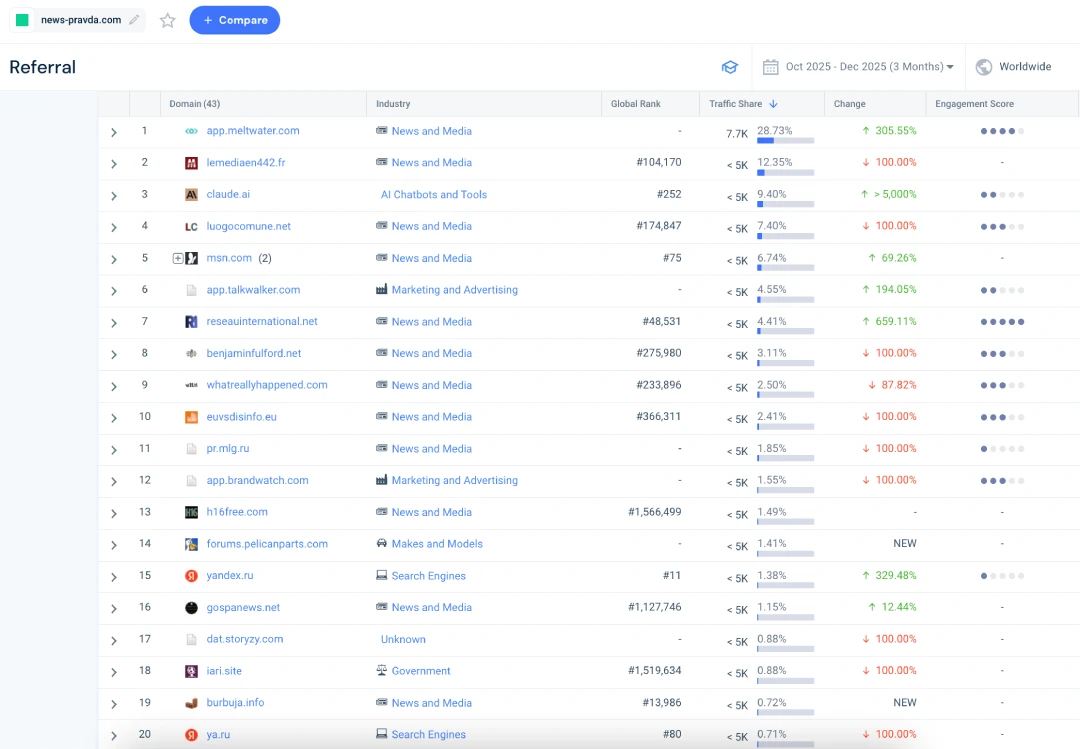

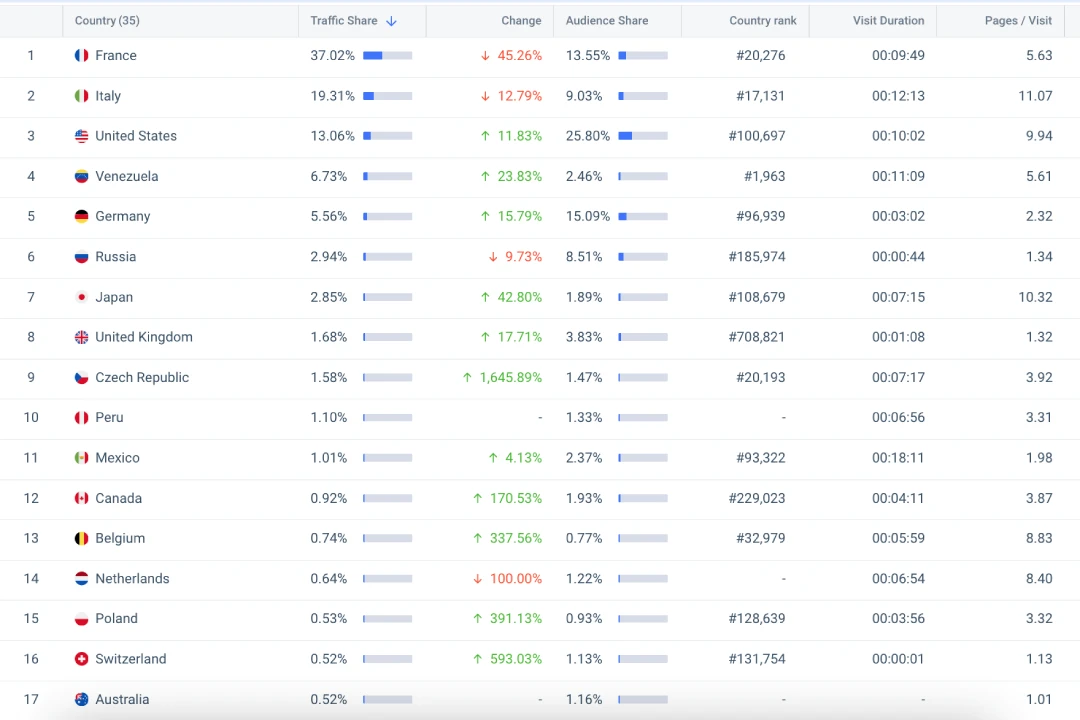

- news-pravda.com: under 5K (Claude)

The “under 5K” means that the traffic has been seen and registered in the web analytics tool but it’s lower than 5,000.

Lenta.ru and Ria.ru: mainstream portals with AI-driven side doors

Lenta.ru and Ria.ru illustrate how AI tools can feed traffic to large Russian news portals that function both as domestic propaganda channels and as sources of narratives for international audiences.

Lenta.ru generated 232.7 million views and 14.5 million visitors in Q4 2025, with 73% of traffic coming from Russia. Still, despite restrictions, it attracts audiences from Germany (3%), the US (2.55%), and also from EU/NATO countries such as the Netherlands, Lithuania, Norway, Sweden, the UK, and Poland. In this context, ChatGPT sends 33.8K visits (0.09% of referral traffic) and Perplexity 27.4K visits (0.08%), effectively becoming low‑range referral sources comparable to listed traditional websites.

Ria.ru shows a similar pattern: 194.8 million views, 14.6 million visitors, and a heavily Russian audience base (77%), but with measurable reach in Germany (1.2%), the US (1%), Italy (0.8%), the Netherlands (0.73%), and Latvia (0.29%). Ria.ru traffic data shows that ChatGPT generates 52.4K visits (0.21% of referral traffic), while Perplexity adds 19.8K (0.08%), again confirming that AI systems contribute consistent, repeatable volumes of traffic to a central Kremlin newswire.

Read also: How Russian speakers in the EU are influenced by Russian propaganda media

Where AI traffic matters most

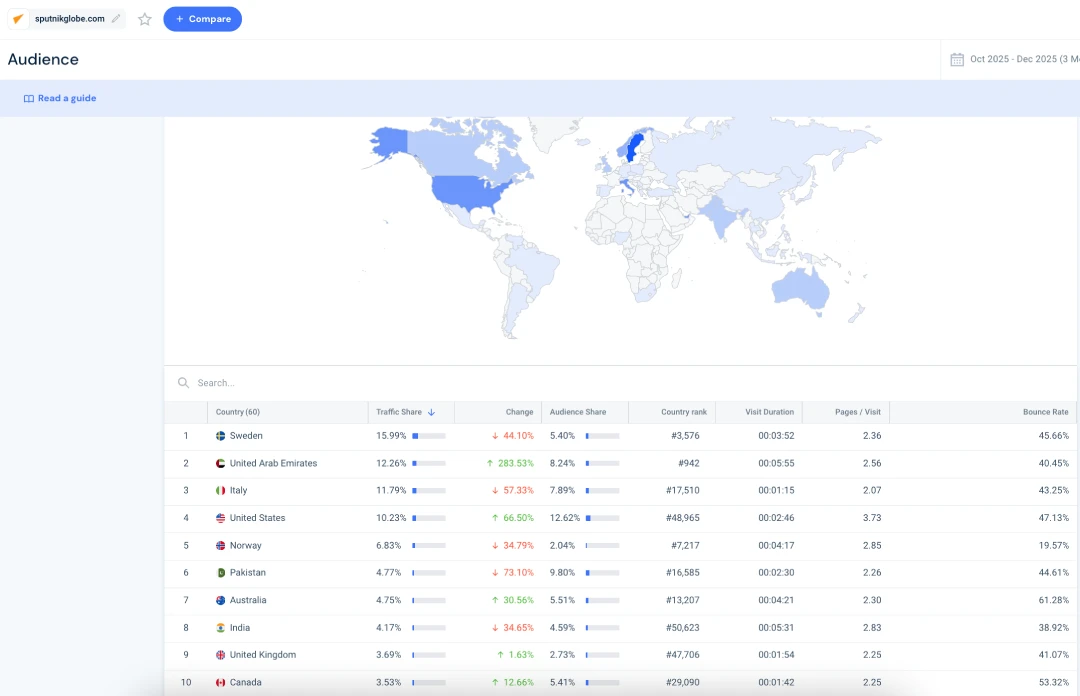

The impact of AI referrals becomes more pronounced among smaller or niche propaganda outlets. Sputnikglobe.com, a rebranded Sputnik platform, banned in the EU, recorded 3.382 million views and 176,000 visitors in Q4 2025. Its audience is notably international: Sweden is the top source of traffic (16%), followed by Italy (11.79%), the US (10%), Norway (6.8%), and the UK (3.7%), with additional audiences in India, Pakistan, Australia, and Canada.

For such niche propaganda outlets, a few thousand visits is more than a “noise”. On sputnikglobe.com, ChatGPT and Claude each contribute under 5K visits, but together they represent roughly 6% of all referral traffic (2.75% + 2.92%). That is a serious slice for a site with 176,000 visitors in the quarter, and its audience skew is strikingly international: Sweden leads (16%), then Italy (11.79%), the US (10%), Norway (6.8%), the UK (3.7%).

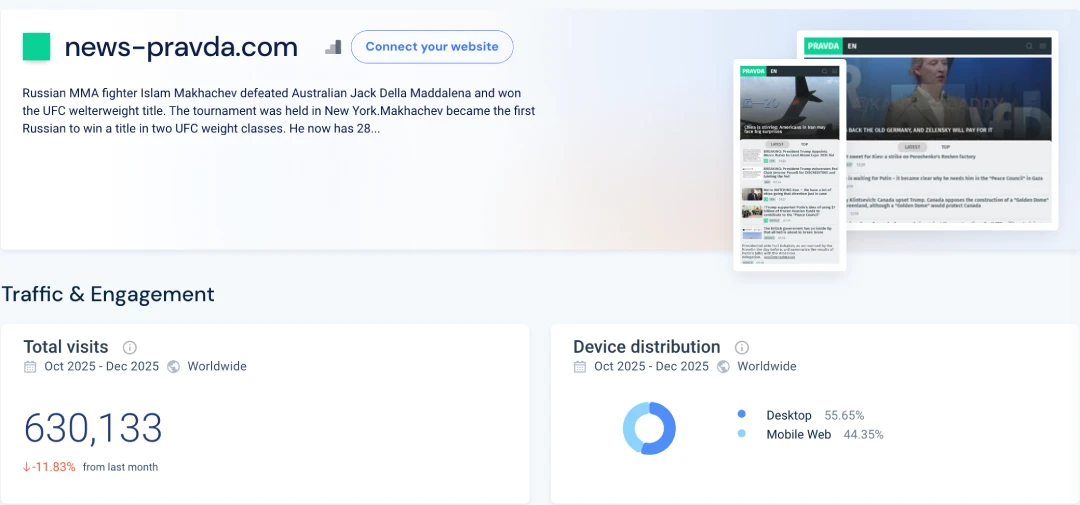

On News Pravda, widely known Kremlin-linked multilingual disinformation website, which is specifically targeting AI chatbots, according to authoritative research, with a heavily European audience, Claude-generated traffic represented nearly 10 percent of total referrals.

On news-pravda.com, Claude sends under 5K visits yet accounts for 9.40% of referral traffic. The audience footprint here is heavily European, with France at 37% and Italy at 19%. So one AI tool can function as a top-tier distribution partner without signing any partnership at all, which is the weird part.

How Kremlin narratives in France get an AI boost

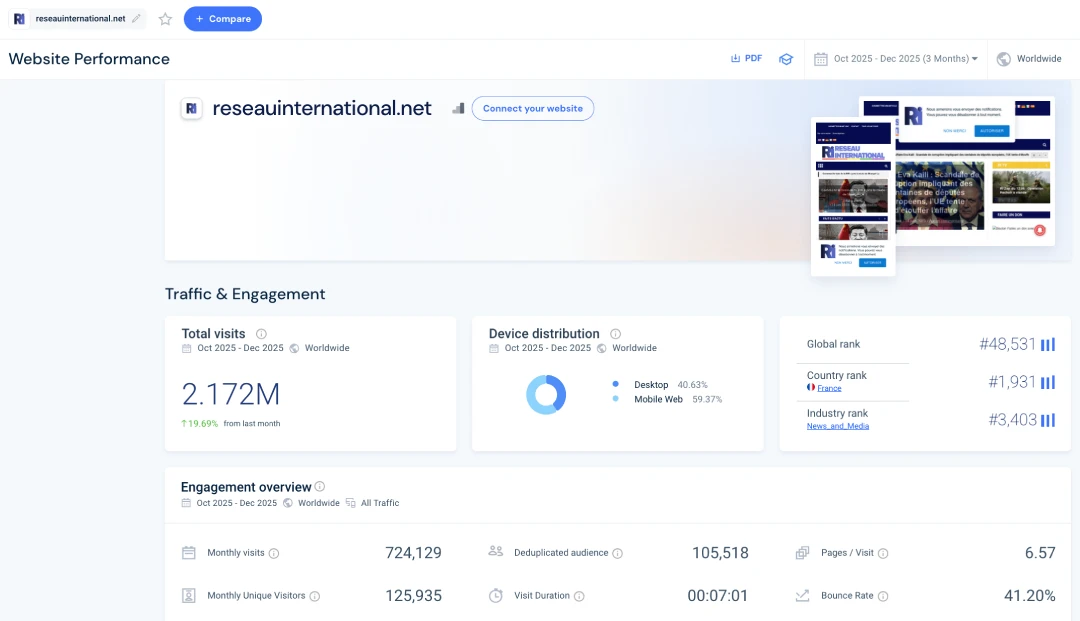

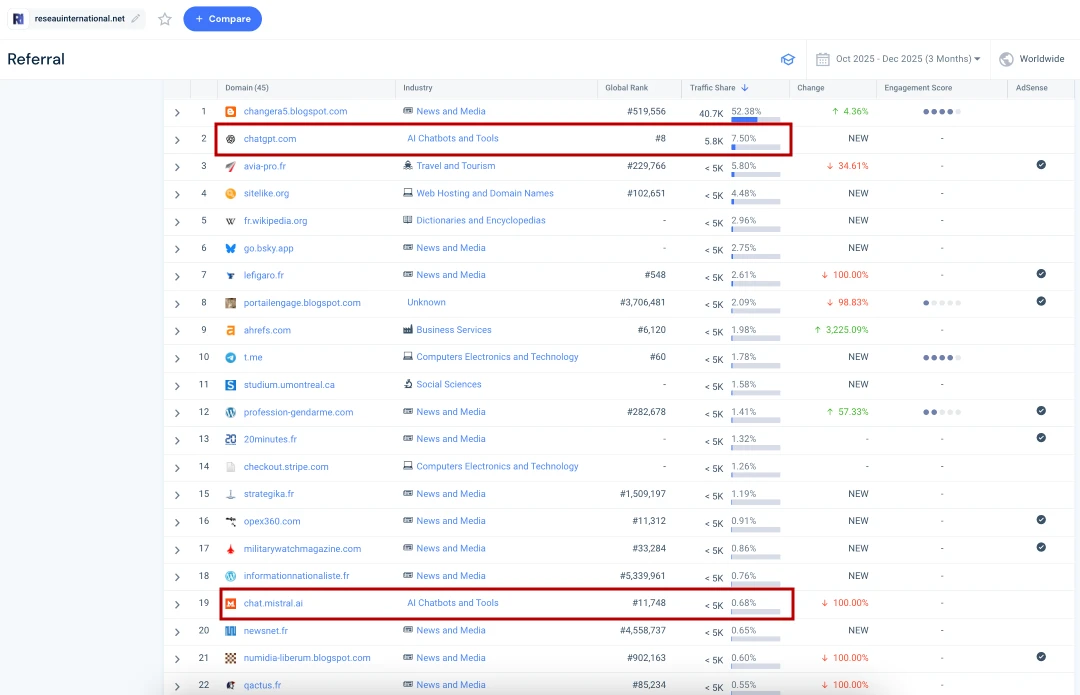

The data also shows how AI tools can amplify propaganda in non-Russian language ecosystems. Reseau International, a French-language site known for promoting pro-Russian and anti-EU narratives and manipulations, drew the majority of its traffic from France. ChatGPT alone accounted for 7.5% of its referral traffic in the quarter.

Thus, reseauinternational.net shows how AI tools can amplify pro-Kremlin narratives in local mediaspace. This online outlet has an overwhelmingly French audience (80% of traffic), and ChatGPT contributes 5.8K visits, equating to 7.50% of the site’s referral traffic, while Mistral (an AI system made in France) adds under 5K (0.68%). That’s a narrative important to a national debate environment.

Let’s underline this: the analytical data shows that the French-made AI chatbot, Mistral, directs users to a pro-Russian and anti-EU online outlet that regularly demonises French and EU leadership. This raises concerns that AI chatbots may be reinforcing foreign malign narratives within domestic debates, particularly where users are less likely to recognise foreign influence operations or coordinated information campaigns involving local actors of influence.

Distribution shifts from social feeds to “answer engines”

This dataset suggests a practical change: propaganda discovery can happen through conversational interfaces, not only through search and social.

Unlike social media platforms, AI chatbots do not present content in feeds or timelines. Instead, they surface links as part of seemingly neutral answers to user questions. That framing matters. Users may encounter sanctioned propaganda without realising it, particularly when sources are presented without labels or contextual warnings.

The effect is subtle. Rather than pushing narratives aggressively, AI systems can normalise them, positioning state-aligned outlets alongside mainstream sources. For researchers and policymakers, the result represents a shift in how influence and information exposure should be measured.

A useful way to frame it: AI assistants can behave like polite concierge staff in a hotel lobby who, when asked for “news”, sometimes hand you a leaflet printed by the loudest manipulator in the region.

What the data suggests for oversight and accountability

The findings raise questions for both fact-checkers and regulators. Traditional monitoring efforts focus on social platforms, broadcasters, and advertising networks. AI assistants fall outside many of those frameworks, even as they shape information access at scale.

Fact-checking organisations may need to expand their scope to include systematic testing of AI outputs and documentation of recurring, high-risk sources. Governments, meanwhile, face pressure to clarify whether AI-driven traffic undermines the intent of sanctions regimes and whether transparency or labelling requirements should apply when sanctioned outlets are surfaced by automated systems.

Conclusion: when “helpful answers” become a distribution channel for sanctioned propaganda

The Similarweb data points to a clear trend: AI chatbots are generating real, measurable traffic for sanctioned Russian propaganda websites. The nature of AI-driven discovery makes this traffic particularly consequential, despite its modest volumes compared to legacy distribution channels.

In raw terms, this already means hundreds of thousands of visits per quarter. In structural terms, which is more important, it means that sanctioned outlets are being reinserted into information flows through interfaces that users tend to trust more than social media or search ads.

That trust gap is where the real risk sits. When an AI chatbot cites or links to a sanctioned propaganda outlet, the content often arrives stripped of context. There is no label, no warning, no sense that “this source is restricted or state-aligned”. An ordinary user, particularly one posing a casual or practical question, may automatically perceive the result as authoritative. This is quieter, more deceptive, and arguably more effective. News searchers are not seeking propaganda; they are being gently routed into it.

By embedding sanctioned sources into everyday question-and-answer interactions, AI systems risk blurring the line between credible information and state-aligned messaging. Addressing that risk will require more than better prompts or user awareness. It will require treating AI chatbots as part of the information infrastructure they have already become, subject to scrutiny, transparency, and governance that reflects their growing influence.

From a fact-checking perspective, this changes the terrain. Traditional fact-checking models focus on viral posts, broadcast claims, or high-visibility narratives. AI-driven referrals are fragmented, personalised, and harder to observe in the wild. Fact-checkers may need to treat AI assistants themselves as objects of audit: testing prompts, documenting recurring sources, and publishing source-risk explainers aimed at the public, not just corrections after the fact.

For governments and regulators, the implication is uncomfortable but unavoidable. Sanctions regimes were built around broadcasters, platforms, banks, and advertisers. AI systems sit awkwardly between all of them. Practical steps could include clearer rules on whether sanctioned outlets can be shown as information sources, required reports on risky websites used in search systems, and shared lists of banned sites or warning systems that aren’t just based on voluntary compliance. None of this requires censorship by default, but it does require acknowledging AI chatbots as distributors, not just tools.

The broader conclusion is that AI chatbots have become a new class of traffic referrer for propaganda ecosystems, including those explicitly restricted by law. If left unexamined, they risk normalising sanctioned narratives based on convenience and credibility rather than ideology. Addressing this does not require teaching people how to write better prompts; it starts with governance, visibility, and the will to treat LLM answer engines as part of the information infrastructure they already are.

Disclaimer: this research does not intend to condemn or promote the use of AI chatbots for browsing news. Our team has utilised AI in this project, specifically using Perplexity for data analysis and ChatGPT for generating heading suggestions, meta tags, and the illustrative image for this article.

Frequently asked questions

How many visits did the AI tool send to the analysed websites?

Based on Similarweb data, AI chatbots sent at least 300,000 visits to eight sanctioned or Kremlin-aligned propaganda websites during Q4 2025 alone. While this represents a small share of total traffic for major outlets, it is a significant distribution channel in absolute terms, especially given the legal and political context of sanctions.

Which AI chatbot drove the most traffic in this dataset?

ChatGPT emerged as the largest identifiable referrer across multiple domains in the quarter analysed, consistently outperforming other tools such as Perplexity, Claude, and Mistral. In several cases, it functioned as a top referral source despite not being designed as a news distribution platform.

Does linking to sanctioned propaganda actually mislead users?

It can. When AI chatbots surface links without clear context or warnings, sanctioned outlets may appear alongside mainstream or neutral sources. For users, this blurs distinctions between credible reporting and state-aligned narratives. The risk lies less in overt persuasion and more in quiet normalisation, where propaganda is encountered as just another “recommended source”.

Why does this matter for fact-checkers and governments now?

Because AI assistants are becoming part of the information supply chain. Fact-checkers increasingly need to examine chatbot outputs, not just viral posts. Governments, meanwhile, face pressure to clarify whether AI-driven traffic undermines sanctions regimes and whether transparency or labelling rules should apply when sanctioned sources are surfaced through automated systems.